Welcome to the April edition of CLAMOR! For this month, I gathered some reflections on quiet and silence (spoiler: it can be quite loud), and all the noise that makes no sound. Plus, the accidental guru, birds with road rage, and a Clamor event.

In the 1990s, the Norwegian explorer Erling Kagge became the first person to reach both Poles and the summit of Mt. Everest unassisted. Years later, in his book Silence in the Age of Noise (2018), he reflected on the weeks he spent alone crossing Antarctica.

“At home, there’s always a car passing, a telephone ringing, pinging or buzzing, someone talking, whispering, or yelling. There are so many noises that we barely hear them all,” he wrote. “Here it was different. Nature spoke to me in the guise of silence. The quieter I became, the more I heard.”

In the absence of everyday noise, a myriad sounds rushed to fill the sonic vaccuum—the wind as it came and went and sometimes whistled, the crunch of snow beneath Kagge’s footsteps, the deep seismic hum of the ice sheet, and the sustaining rhythms of his breathing and beating heart. At the same time, a fascinating and ever-changing display emerged from the “visual silence” of the exceedingly flat and white vista spreading for miles in all directions.

“The ice and snow formed small and large abstract shapes,” Kagge recalled. “The uniform whiteness was transformed into countless shades of white, tinged with blue on the surface of the snow, or somewhat reddish, greenish, and slightly pink.”

I’ve read a lot of reflections on silence in the last few years, and a couple themes echo through many of these writings—whether by Zen masters, Trappist monks, composers, sound-designers, or neuroscientists. First, we don’t experience silence as a true absence, but something more like an expansion in auditory perception, reaching out and newly receptive now that we’re no longer bombarded by noise. Second, the noise that silence-seekers most sought to escape was not defined by loudness but by its assault on our attention. And this sort of noise need not be audible at all.

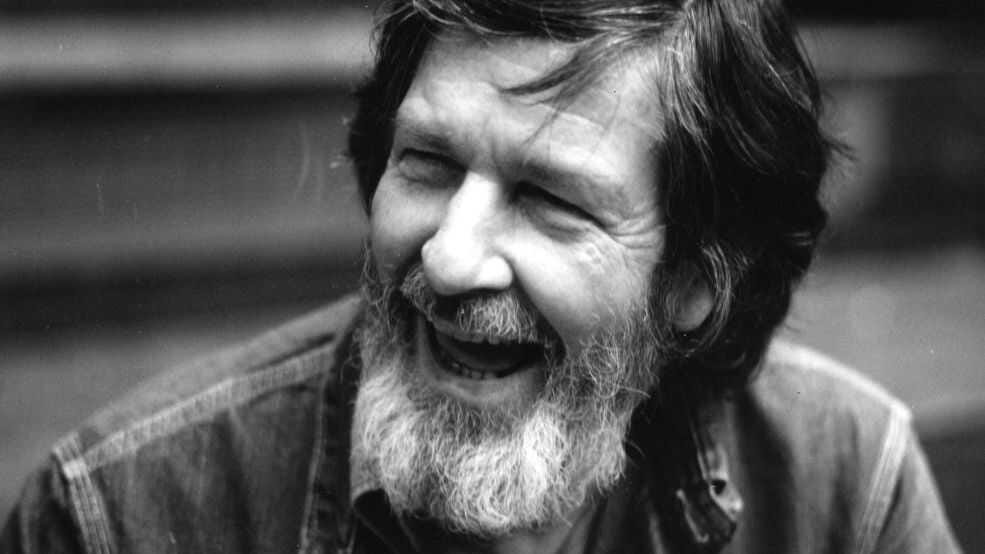

“When we confront silence, the mind reaches outward.”-John Cage

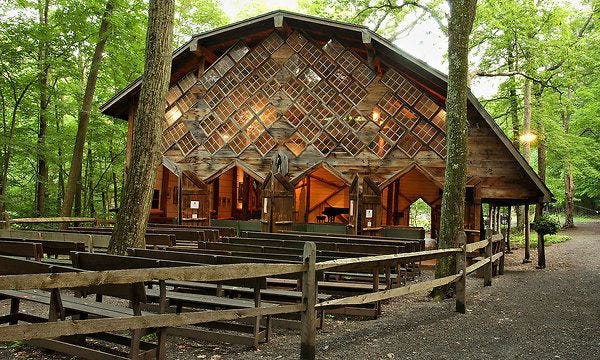

The Maverick Concert Hall is a barn-like structure built in 1916 of rough-cut oak and pine timber with a sloping gambrel roof situated in a woodsy area near Woodstock, New York. On a late August evening in 1952, a crowd gathered here for a performance by the virtuoso pianist, David Tudor.

Among the pieces Tudor would perform was the premier of 4’33” by the avant-garde composer John Cage, which the audience would soon discover was four minutes and thirty-three seconds without a note being played. Dismissed by many serious musicians and critics (then and now) as a gimmick, 4’33” is among the most famous demonstrations that silence is simultaneously impossible yet immensely powerful.

At the concert hall, Tudor approached the piano with his usual gravitas, sat down, opened the keyboard lid, and did nothing for 30 seconds. Then he closed and reopened the lid and waited another 2 minutes and 23 seconds before closing and reopening the lid again and waiting for 1 minute and 40 seconds. When the final seconds ticked away, Tudor closed the lid a final time, stood up, and walked off stage.

Despite the lack of notes, the performance was far from silent. In the first movement, “you could hear the wind stirring outside,” Cage recalled. “During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof.” By the third movement, people shifted uncomfortably in their seats, grumbled complaints, or walked out in frustration.

Structurally, the silent beats of a composition are the purest measure of time, which Cage believed to be the most fundamental musical ingredient. With 4’33” the passage of time was a constant, like an empty glass into which any sound or silence could be poured.

On that late summer evening in the Maverick Concert Hall, an audience listened to itself. They likely sensed the tension in the creaks of shifting seats and clearing throats, as the pianist waited, and they waited. They may even have felt wonder—what the hell is this about and what will happen next—just as they noticed the wind rustling the trees and the first raindrops pattering on the roof.

In May 2000, NPR’s All Things Considered told the story of that evening and Cage’s exploration of silence and listening (below is a rebroadcast from 2012).

What is the deepest silence you have ever known?

That was the central question posed by Justin Zorn and Leigh Marz at the opening of Golden: The Power of Silence in a World of Noise (2022). The book was born from a 2017 article they co-authored in the Harvard Business Review, which went viral, about the increasing importance of cultivating “quiet time” in busy lives. Zorn and Marz asked people from all walks of life about their deepest moments of silence, and they were struck by how many of these memories were filled with sounds, some of them quite loud—babies being born, a summer forest suddenly alive with cicadas after a 17-year absence, kayaking a clean line through roaring rapids, or losing oneself in chest-thumping rhythms on a crowded dance floor.

To make the case that the world is getting noisier, many writers (including me) will cite decibel-based evidence, such as spikes in restaurant loudness, the need to crank up emergency sirens across the decades to overcome the rising city din, or the vanishing of natural quiet. But arguably the biggest noise problem we face is the noise that shatters focus, an onslaught of unwanted signals at any decibel level, including zero. The most challenging quiet to achieve is a quiet mind.

The connections between audible noise and what Princeton University historian Emily Thompson dubbed the “online cacophony” of overstuffed email inboxes and endless social media scrolls is more than metaphorical. Not only do our digital notifications lay claim our attention with a growing menu of pings, beeps, and chimes, but an overload of signals—audible or not—depletes our limited attentional resources in many of the same ways.

Unfortunately, we have a love-hate relationship with the noise of distraction. As much as we crave quiet, we also kind of fear it. For instance, according to a 2014 study by researchers at the University of Virginia and Harvard, people would rather administer painful electric shocks to themselves than sit silently in a room, alone with their thoughts for 15 minutes.

As the explorer Erling Kagge recalled from his days on Antarctica, “The biggest challenge is to get up in the morning when the temperature is fifty degrees below freezing. The next hardest challenge? To be at peace with yourself.”

The noise that scatters our attention can be exhausting. Yet we still crave the quick bursts of dopamine from scrolling social media and letting our thoughts skip along on the surface of our consciousness. What are we missing out on? What’s being left unsaid? What uncomfortable or awkward thoughts might rush in to fill that silence?

“Even if we are not talking with others, reading, listening to the radio, watching television, or interacting online, most of us don’t feel settled or quiet,” wrote the Vietnamese Buddhist monk and peace activist, Thich Nhat Hanh, in his book Silence. “This is because we’re still tuned to an internal radio station, Radio NST (Non-Stop Thinking.”

Recognizing the challenge of reclaiming our scattered attention, Hanh suggested people try a “walking meditation…to clear the mind without trying to clear the mind.” You don’t say, “Now I am going to practice meditation!” or “Now I am going to not think!” he continued. “You just walk, and while you’re focusing on the walking, joy and awareness come naturally.”

When I am liberated by silence, when I am no longer involved in the measurement of life, but the living of it, I can discover a form of prayer in which there is, effectively, no distraction. My whole life becomes a prayer. -Thomas Merton, Trappist monk, theologian, and social activist, Thoughts on Solitude (1956).

Attention Restoration

When we tune out the noise, we can tune in something else. Nature, for instance, is filled with sounds that can help quiet the mind. According to “Attention Restoration Theory,” developed in the late 1980s and early 90s, by Stephen and Rachel Kaplan, then environmental psychologists at the University of Michigan, our minds recharge when our attention gets captured by the right kind of stimuli—engaging but not demanding or alarming, offering a bit of surprise but within a broader pattern of familiarity and safety. Nature has plenty of acoustic hooks that hit this attentional sweet spot that Kaplan’s called “soft fascination,” ranging from birdsong to the splashes of a cascading stream.

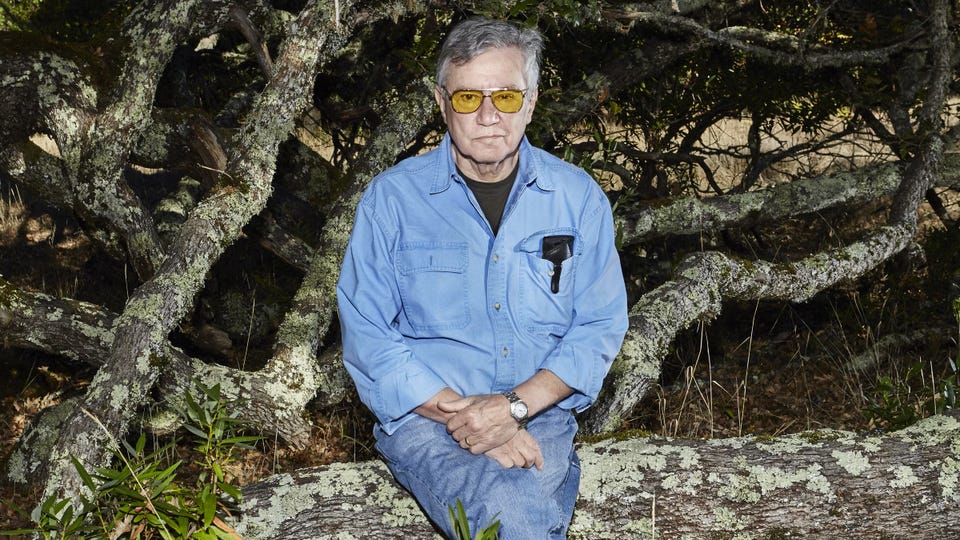

With that in mind, I’ll close this post with the story of Bernie Krause , who has been a renowned collector of nature’s soundscapes for more than half a century. He’s authored several books, including The Great Animal Orchestra (2012) and The Power of Tranquility in a Very Noisy World (2021), and his recordings have been featured in zoos, aquariums, films, TV shows, and multimedia museum exhibits.

But, before all that, in October of 1968, Krause was a 30-year old pioneer in electronic music. One afternoon, he found himself driving across the Golden Gate Bridge up to a woodsy suburban park. All Krause knew was that he needed to collect some nature sounds so he and fellow musician, Paul Beaver, could mix them into an ecology-themed, synth-heavy album called In a Wild Sanctuary. He had no plan. He didn’t know much about nature. Truth be told, he was a little scared of it. He certainly didn’t know that he was about to change his life.

In the late 1960s, the duo of Beaver and Krause made far-out music with what was then the latest technology, Moog synthesizers, an instrument they also sold as the company’s west-coast sales reps. After demonstrating the Moog from a booth at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, Beaver and Krause were suddenly much in demand, selling synthesizers and playing them as studio musicians for major bands like the Byrds and the Doors who were pushing a new wave of psychedelic rock.

They signed a record deal with Warner Brothers in 1968, and according to Krause, whom I interviewed by email and phone in the spring of 2021, the inspiration for Wild Sanctuary was kind of a fluke.

“I didn’t know what ecology was back then,” Krause told me. “But we had no other ideas.”

So, toting a couple of stereo microphones, a headset, and a portable tape recorder, Krause set off into the park. He marched down a trail away from any sounds of traffic, until he reached a small stand of redwoods where he stopped, slipped on the headphones, and pressed record.

It wasn’t an ideal time to listen. A lot of the migratory birds had already moved along. After months with little rain, the nearby stream was reduced to a barely audible trickle. A breeze rustled the tree canopy, and then a pair of ravens passed overhead, Krause recalled in an email, describing, “the edge tones of their wingbeats and occasional three-beat caws lowering in pitch slightly with each statement as they distanced themselves from my mics.”

But the scarcity of sounds didn’t matter nearly as much as how listening made Krause feel. He had spent a lifetime battling a chronic state of agitation and distraction, which was belatedly diagnosed as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Those first few moments of listening to nature offered him the first real relief. It settled his mind and soothed his anxiety.

“As soon as I switched on the recorder, the impact of that delicate acoustic fabric and space that I heard was so stunning and emotionally powerful,” he told me. He could still only manage a minute of quiet listening before he’d ruin the recording by slapping at mosquitos or shuffling his feet. But the effortless engagement he felt with the natural world as he listened to it had hooked him. He kept making recording trips into the field, and each time, he was able to stay still a bit longer and lose himself deeper in the rush of sounds filling his ears.

In the decades that followed, Krause would devote his life to nature listening, amassing more than 5,000 hours of soundscapes, and advocating on behalf of habitats around the world threatened by noise and other human endeavors such as clear cutting and climate change. But it wasn’t science, environmentalism, or aesthetics that kept Krause returning to nature for more listening. “The reason I do it,” he said, “is because it makes me feel good.”

Wait…What?!

Acoustic Odds and Ends

As detailed above, sometimes the “noisy” experience is our ultra-low-decibel scrolling through social media, distracting ourselves with its ephemera and outrage-bait, while a higher-decibel woodsy walk beside a rain-swollen river gives us a “quiet” feeling of calm, clarity, and receptive attention. I thought about this the other day when I caught myself checking Instagram while watching TV and, ironically, this video of comedian Des Bishop’s musing on mindfulness popped into my feed (warning, naughty words):

In 2017, after Bernie Krause had spent decades immersing himself in natural soundscapes that soothed his psyche, he encountered a new and terrifying natural sound—the roar of a wind-fueled wildfire that forced him and his wife to flee their California home. The fire consumed their house along with a treasure trove of recordings. Recently, the New Yorker online featured a documentary called The Last of the Nightingales by filmmaker, Masha Karpoukhina, about Krause and what our planet’s ecosystems can tell us through the sounds they make, including/especially the scary ones.

Traffic noise is on the rise in the Galápagos Islands of all places, and a recent study found that the growing raquet makes the male Galápagos yellow warbler more aggressive and confrontational when he hears another warbler singing in his territory. “Communication usually is in lieu of physical aggression,” one of the co-authors explained in an article about the research in The Guardian, “but if the communication is not possible because of noise, then they might actually engage in risky behaviours that would lead to a physical fight.”

If you’ll be in the Boston/Cambridge area on May 21, 2025, please join me at the Harvard Book Store for a Clamor book launch event at 7 PM. I’ll be talking noise and soundscapes with Dan Gauger, one of the acoustic pioneers who created the first Bose noise-cancelling headphones and other products. No tickets required, just show up and say hi. (Also, a reminder that the good folks at Tertulia are offering offering a big discount for preordering the book here.)

Thanks so much for reading CLAMOR! Please spread the word and subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.