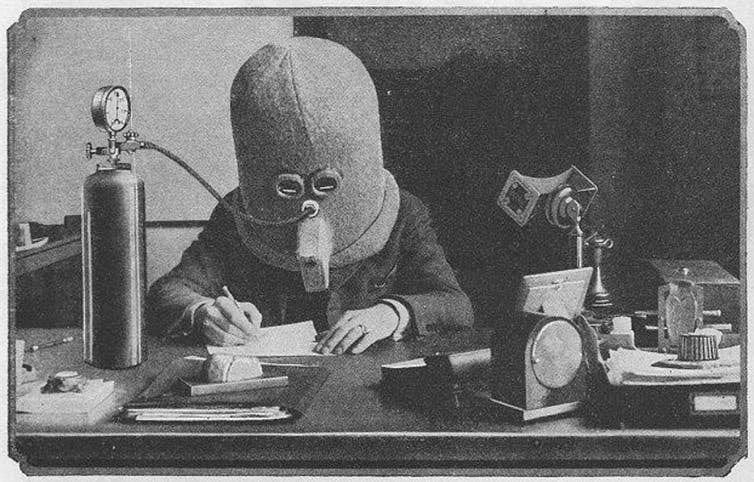

The return-to-office (distraction), the city founded to fight noise, and the year we almost stopped listening to national parks.

Plus some acoustic odds and ends for your enjoyment

Welcome to the September edition of CLAMOR! This month: Can better sound environments beat mandates in the return-to-office push? A rural Texas community wants to form a new city to battle bitcoin noise. Protecting national park soundscapes in an era of shrinking budgets. Plus, the tired songs of birds kept awake by noise, the missing sounds of endangered species recovery, a bit of book news, and Munich officials work with soundscape researchers for healthier greenspaces.

Can we return to the office but leave the noise behind?

With summer vacations behind us, students are being called back to the classroom, and their parents are increasingly being called back to the office. Companies are still struggling to find the right post-pandemic balance of workplace flexiblity, and one of their biggest obstacles is office noise.

Office noise isn’t new, but it grew from an occasional nuisance into a pervasive workplace problem during the open-plan office boom of the early 2000s. Spurred by the bright, modern headquarters of emerging tech giants, companies in every sector raced to remove walls and sound absorbing materials, to escape—at least aesthetically—the hidebound, hierarchical workplaces of the past. Open-office enthusiasts predicted that collaboration and breakthrough ideas would quickly bloom in these barrier-free spaces. At the same time, open-plan offices squeezed more employees into less square footage, which helped the bottom line.

But when the office-noise problem grew bothersome enough to be rigorously studied, researchers discovered that the promised collaboration boost was often a bust, partly due to the din and the lack of speech privacy that ironically led people to communicate more digitally rather than face-to-face. In survey after survey, exasperated workers reported retreating from the cacophony as best they could by donning noise-cancelling headphones, taking more breaks, and generally becoming less productive.

Then Covid hit, and the cacophonous offices emptied and went quiet. Working from home wasn’t always easy (or even possible for many) but people not only adapted, they enjoyed the added autonomy and flexibility, including more control over their sonic surroundings. In the post-Covid world, as more and more workers returned to the office, the noise problems they encountered were not quite the same ones they’d left behind. In many ways, they were worse.

There were several reasons for this. For one thing, companies often downsized office spaces that were no longer serving all their workers all of the time and instituted more shared workstations.

“A lot of companies have renegotiated their leases. They have optimized their square footage,” noted Flore Pradère, the Paris-based research director for global work dynamics at JLL (Jones Lang LaSalle), the global commercial real estate and investment firm. “But the result is that you come back to a much denser work environment where you have many more interruptions.”

In addition, these interruptions now included ubiquitous video-conferencing—the pandemic necessity is now taking up about a quarter of all the time people spend in the office, according to one of the recent survey studies by Pradère and colleagues. Importantly, a more sparsely attended open-office isn’t necessarily a sonic solution because stray conversations can be even more distracting without the usual background churn of workplace sound.

Finally, Pradère noted, employee expectations have shifted in the post-Covid era. Remote workers, she said, “got used to being able to focus on a task and to choose when they could be interrupted.” Even though employees surveyed by JLL agreed that sharing space is helpful for teamwork and collaboration, they still spend half their time on tasks that require focus, and they want offices that support that work.

The collision of heightened worker expectations with noisy office realities has fueled the market for small soundproof booths with names like Zen Box and Thinktanks. Even the much-maligned cubicle has been making a comeback. Meanwhile, a growing awareness that office noise hurts productivity and hastens burnout has spurred demand for acoustic consultants and workplace soundscaping that aims to not only mask noise but support attention and reduce cognitive load and stress.

Despite these efforts, noise continues to hinder the larger return-to-office push. A recent article in Facilities Management Journal covered the survey responses from more than 2,000 office professionals in the UK, in which 36 percent said that they worked from home to escape the noise, and nearly half said they struggled to concentrate when working in the office due to the din.

The press has been rife with stories of return-to-the-office mandates sparking revolts such as “coffee badging” in which people swipe in to the office just long enough to show their face and drink a coffee before sneaking out to get work done in a quieter place with fewer interruptions. The office dodging has led to more employee monitoring and scolding at companies like Samsung and Amazon.

Headlines aside, research by JLL and others suggest that full-time office mandates remain a minority in the corporate world (only one third of firms in the United States require full-time office presence, and the rest have some degree of workplace flexibility, according to latest “Flex Index” published by the workforce research and advisory firm Work Forward.

Some degree of hybrid work appears here to stay, and paying attention to office soundscapes and other environmental factors will be key to making these arrangements succeed, Pradère told me. Earlier this month, JLL published their 2025 Workforce Preference Barometer, based on a survey of 8,700 office workers in 31 countries.

“We saw that environmental factors, especially acoustics, light, temperature, all those aspects are really important to their overall assesment of the workplace,” she said. They found that 84 percent of people who gave their workplaces high marks were also happy with their company’s hybrid attendance policies. Whereas, 48 percent of people who were unhappy with their workplaces felt negative about the office attendance policies.

“The most advanced companies are providing access to a diversity of atmospheres and places in their offices,” she said. Through a mix of planning, creative scheduling, and careful design, “these companies are creating some very active and lively places, some places for more focused work, and even some places for restoration and regeneration.”

We built this city. We built this city…on a dull roar that never stops.

Mitchell Bend, Texas could be the first city founded to fight noise. In November, the residents of this unincorporated community in Hood County will vote on a ballot measure to create a new municipality, giving its residents the power to pass a noise code that could target the noise from the bitcoin mine they say is keeping them awake and making them (and their animals) sick.

The bitcoin operation is located about 10 miles south of Granbury, Texas (outside of Fort Worth). Last year, a group of locals partnered with the environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice to sue the bitcoin facility’s owner Marathon Digital Holdings, Inc. (MARA holdings) over the noise.

I spoke to one of the defendants, Danny Lakey, by phone. The 56-year old Lakey and his wife moved from the city of Arlington to run a hospice in Granbury, and they bought a place on 8.5 acres that they intended to be their “forever home” in a peaceful rural area.

“We have a cattle ranch across the street, so it’s about 350 acres of nothing,” Lakey said. “When we’re looking out, we’re looking at a big valley, and we get to watch gorgeous sunsets and just enjoy the country life.”

But this bucolic scene is just half a mile from the bitcoin mine, and Lakey says the constant noise has kept him and his wife from sleeping well for the past two years. He regularly measures the sound from a spot out near his barn, and he said the noise peaked at 82 decibels but have settled to between 71 and 74 decibels after MARA changed to quieter, liquid-immersion cooling (note: The World Health Organization recommends that noise at night stay below 45 decibels for healthy sleep).

Lakey said the push to create a new municipality followed the realization that they couldn’t count on county, state, and federal authorities to help them mitigate the problem in a place where the economics, infrastructure, and policies are all lining up to bring more bitcoin mines and data centers.

If you’re looking for a place to build these facilities, “we’ve got your water and your power. We have cheap land and low regulations, a state that wants you and a federal government that says it needs you,” Lakey said. “So that is why we feel the need to incorporate, because if we don’t, we are going to be buried in pollution and noise.”

The company did not respond to my request for comment on the noise complaints or the efforts to create a new town. But, they did issue a statement in response to an Axios story about the controversy, which highlighted the soundwalls and other sound-dampening improvements they’ve invested in since acquiring the facility in 2024.

“We are committed to maintaining our health and safety standards at the Granbury data center and being good neighbors,” read the statement. It also noted that multiple sound studies, “have confirmed that MARA’s facility operates well below state and county law noise limits.”

That last bit is a familiar refrain. As I noted in my February newsletter, there’s a mismatch between loudness-based noise laws and the sounds emanating from bitcoin mines and data centers. For instance, Texas nuisance law sets 85 decibels—lawnmower loud and a danger to hearing—as a threshold for “unreasonable” noise. While some neighbors of MARA’s bitcoin mine claim they have clocked sounds at or above that level, the potential health harms of crypto and data center noise is less about absolute loudness and more about the fact that it never stops, disrupting sleep and triggering chronic stress.

This constant noise is also dominated by lower-frequency sound energy, which carries farther than higher frequencies, more easily penetrates walls and windows, and is discounted by the “A-weighted” decibel measurements that dominate most noise ordinances. Lawmakers have begun to recognize this disconnect. Earlier this year, for example, legislators in Virginia passed a bipartisan bill to tame their ubiquitous, low-frequency noise of the data centers spreading across the state, but Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed the measure.

Soundscapes escape a budgetary buzzsaw (for now)

As the fiscal year comes to a close this month, the National Park Service’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division (NSNSD) seems poised to survive into FY2026, despite the administration’s request to slash 50 percent of the stewardship funding that supports the division among other programs. The House and Senate appropriations bills currently keep the 2026 NPS funding levels nearly on par with this past year (The NPS budget in FY2025 was about $3.3 billion, with approximately $375 million for resource stewardship).

It’s worth remembering that the founding charter of NPS in 1916 included the parks’ soundscapes among the natural resources the new agency was mandated to protect. However, NPS didn’t truly listen to these soundscapes until 2000 with the creation of the Natural Sounds Program (that became NSNSD in 2012) to rigorously record and analyze the park soundscapes and provide technical expertise on efforts to protect the parks from noise pollution. Since that time, the study of natural soundscapes has rapidly grown from a niche concern into the expanding field of bioacoustics that has become inextricably linked with nature conservation writ large.

We can learn a lot about ecosystems by listening to them. Networks of small, durable sensors can capture the sonic life of a forest, a desert plateau, or a coral reef from every direction, emanating from otherwise hidden sources, reaching across vast stretches of space and time—clueing researchers into the presence and migration of keystone species, the varying degree of biodiversity, the success of conservation measures, or the impacts of a warming climate, natural disasters, illegal loggers, and poachers.

Earlier this year, one of the world’s most-ambitious bioacoustics efforts passed a major milestone when the Soundscape Baseline Project completed one-year of 24/7 recordings from six forests around the world—in Ecuador, Peru, Gabon, Germany, Bruei, and the United States. While periodic recordings will continue, the baseline measures amounted to more than 300,000 hours of listening, generating a massive amount of data to be analyzed with the help of machine learning in order to develop a tool for measuring ecosystem change and the effectiveness of conservation efforts.

As a side note: More and more citizen scientists are dabbling in bioacoustics, thanks to initiatives like MySoundscape, described on its website as, “A STEM project to sound-map parks of the world, one community at a time.”

Created and voluntarily led by a Larry O’Gorman, an electrical engineer and expert in digital signal processing at Nokia Bell Labs, MySoundscape is a STEM education platform that introduces high-school aged students to environmental acoustics including classroom lessons and a guide to making objective and subjective soundscape measures of local parks, mapping the results, and potentially using the data for environmental science projects, such as tracking seasonal changes or measuring how trees and landscape buffer traffic sounds and how that changes subjective soundscape perception.

MySoundscape is sponsored by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) North Jersey Section and the IEEE Future Networks Technical Community, and O’Gorman invites teachers or youth leaders interested in the project to contact him at log@ieee.org.

Book News

Clamor received some rave reviews over the summer from New Scientist, Nature, American Scientist, Forbes, and Scientific American.

Next month, I’ll be talking about noise and soundscapes to a business-minded audience at the Authors and Innovators Business Ideas Festival, which will be linked to the Boston Book Festival (more details to come in October’s newsletter). Finally, say hello to Lulu, the latest #ClamorDog!

Wait…What?!

Acoustic Odds and Ends

Humans aren’t the only species to struggle after a night of noise-disturbed sleep, according to a recent study of common city birds published last month by two animal behavior researchers in New Zealand.

Previous studies have found that noise and light pollution disrupt the sleep of birds. To test the impacts of these disturbances, the researchers caught 13 common myna bird in the Aukland area. Over the course of two months, they compared the mynas’ songs following nights when the birds were allowed to sleep in a quiet environment or were kept awake by the researchers continuously moving about the lab and occasionally tapping on their cages.

“After just one bad night of sleep, common mynas sang fewer and less complex songs. They also spent more time resting during the day,” the researchers wrote in an overview of the research published by The Conversation. “Birds that sing more frequently and with a greater complexity can attract better mates and defend territories,” the researchers noted. “Therefore, a poor-quality song can seriously affect a bird’s ability to reproduce and survive.”

The common myna. Tisha Mukherjee/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA Listen below to the common myna singing after a normal night of sleep and then after a restless, noisy night:

There’s a massive silence in the middle of the Canada’s vaunted campaign to curb underwater noise, according to a recent analysis by Canadian researchers. Canada has been a leader in the push for quieter shipping via the International Maritime Organization, and the government published an extensive Ocean Noise Strategy last year. And yet, noise pollution and soundscapes are almost entirely absent from the nation’s efforts to protect endangered fish species.

Specifically, the researchers found only one mention of noise pollution as an environmental threat among the 138 recommendations for listing by Canada’s Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife and none of the 56 plans for species recovery considered the fish's use of sound, the importance of soundscape in its habitat, and the potential threat of noise pollution.

Landmark reports such as the Ocean Noise Strategy are mostly “guiding documents” for regulators but don’t contain anything enforceable, the researchers noted. “Therefore, the most concrete way to mitigate the impacts of noise pollution is to include considerations of noise and species’ use of sound in conservation strategies.”

I emailed lead author, Kiara Kattler, a master’s student in marine ecology at the University of Alberta, who cited research suggesting that reducing noise pollution is helping the recovery of endangered Southern Resident killer whales.

“These studies demonstrate how important noise pollution, and thus noise reduction, is for the sustainability of vulnerable populations,” Kattler wrote. “Our hope is that this work flags noise pollution as an important aspect that should be considered in future conservation and recovery plans.”

Watch this space! An interdisciplinary team of researchers at the Technical University of Munich is collaborating with city officials to study the impacts of urban design choices on the soundscape of city greenspaces and the resulting impacts on citizen health and wellbeing. In this first year of the three-year project, researchers have been leading Munich residents on structured soundwalks through three distinct types of neighborhoods that are slated for major redevelopment within the next decade. They are combining objective and subjective measures of the soundscape with saliva samples to measure stress hormone levels of listeners.

Thanks so much for reading CLAMOR! Please spread the word and subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Hi Chris,

I'm wondering if you can point me in the direction of research or ongoing projects studying the impacts of noise pollution within K-12 schools? I'm a teacher and it's a topic that I think a lot about - I'd love to dive deeper into the topic if possible.

Thank you for your work! It's been profoundly helpful to me.